Before I read Sholem Aleichem, I read Mark Twain. I was eight years old then, and I read it in Russian. I didn’t know that Mark Twain was a famous American humorist, and in fact, I didn’t even know what humor was – until one day I opened that book and read:

“Tom!”

No answer.

“Tom!”

No answer.

“What’s gone with that boy, I wonder? You Tom!”

And even as I type these lines, I smile thinking about the many adventures of Tom Saywer and Huckleberry Finn, who taught me, among other things, that children, too, can be free spirited and enterprising.

My next brush with Mark Twain took place when I turned 39, shortly after we left Moscow for Vienna, Austria. We didn’t really choose Vienna. It was chosen for us by the Hebrew Immigrant Aide Society (HIAS) that helps the world’s Jewry to resettle. There must have been thousands of Russian immigrants there already – some waiting for permission to stay in Europe, some to go to Australia and New Zealand, and many more to enter the United States.

My family arrived in Vienna from snowy and aloof Moscow at the end of February. Somebody met us, dazed and disoriented, at the airport, and drove us to the place that HIAS rented for the waves of new Russian immigrants. There was no snow anywhere, the air was filled with early spring dampness and uncertainty, and the gray sky was reflected in the windows of residential buildings and shopping malls. The city was beautiful, though, with soaring cathedrals, imposing buildings, and museums, spoiled only by numerous dachshunds mincing on their short legs next to their orderly owners along the city streets — the same streets that, in 1938, saw the proudly marching columns of Nazis and the terrified crowds of Jews, who were driven from their homes to, first, clean Vienna’s pavement with forks, spoons, and even their tongues, and, later, transported to the Dachau concentration camp. Of course, we were not desperate like them, but you could not help wondering about the ironies and unpredictability of life.

We stayed there for four months, which wasn’t too bad for a family with no friends or relatives to sponsor its move to America (and you had to have a sponsor to do that), and whose only hope was that HIAS would find somebody willing to sponsor us. It was a strange, shadow-like existence. We were free at last, or, maybe, in a free fall — only time would tell which one it would be. If we had died there, the city wouldn’t have noticed. For one thing, nobody knew us there. For another, no Russian immigrant was allowed to work – at least not legally, and the only source of income we had was the little money that HIAS gave us each month and even the smaller amount we earned ourselves by selling our camera, cotton bedding, and matrioshkis — as well as other Russian souvenirs –at the flea market. And yet, life went on and my daughter even attended school, or what passed for school in that ephemeral existence: a room in the Jewish Resettlement Center, where children of all ages studied together with the teachers who were also in transit — one day the school had a math teacher and the next day she was gone.

And then, one day, somebody called from the American Embassy: “Congratulations! You’ve received an entrance permit. You’re going to Columbia, Missouri.” “Where is it?” “Between St. Louis and Kansas City.”

We hung up the phone and ran to the nearest library. There we found a map of the United States, in the middle of which we spotted a tiny dot for St. Louis and, close to it, another one for Kansas City. Columbia was nowhere on the map, yet the word “Missouri” rang familiar. Wasn’t that the birthplace of Mark Twain? I grabbed a large dictionary. Yes, Samuel Clemens was born and raised in Missouri, and since he went on to become a major American writer, we couldn’t go wrong there, either.

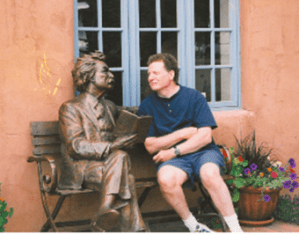

Fast-forward another ten years. This time, I am on vacation in dry and beautiful Santa Fe. We — my American husband, my daughter and her future husband, and I — are walking along the streets edged by blue and yellow adobe houses, admiring their bright colors and front yards landscaped with rocks and cactuses, and stopping at every art gallery. At one intersection, I turn around the corner and, suddenly, come nose to nose with Mark Twain. The great man sits on a bench surrounded by bronze horses, statues of children, and other art objects. His left hand rests on the back of the bench, and his right hand holds an open book. What in the world is he doing in New Mexico of all places?

Well, I never found the answer to that. But that day in Santa Fe, I found an answer to something much more important to me. Some time earlier, I began to venture into writing. Yet to my surprise, it turned out to be very hard, and not only because English was my second language (although that was a big part of it!). There was something else missing in my prose, vital and elusive. I spent hours on my computer. I poured my soul into every phrase (I came from the Russian tradition where “soul” was very important!), yet everything came out dead and full of self-pity. What was wrong? But as I stared at the familiar face framed with a mass of wavy bronze hair, it suddenly came to me. The thing I was missing was humor. Life has many facets, and humor is one of them. It enlivens our life when we perform everyday chores, and it makes our life bearable when we suffer.

It would be wrong of me to say that the sudden encounter with the statue of Mark Twain miraculously improved my writing (in fact, it would take me another five years to publish my first piece), but it definitely helped me find my “voice.”

P.S. Before we left the gallery, I asked my husband to sit next to Mark Twain and took a picture of both of them together. Here they are – two great men in my life!

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born on November 30, 1835, Florida, Missouri. Happy Birthday, Samuel Clemens!

Please click “like” if you like my picture :). Also, tell me about your “role models,” would you?

P.P.S. This is a long post, but if you’re still reading, I’ll confess to you that, originally, I wrote: “Life has many faucets, and humor is one of them,” which my husband had a good laugh about. Now, if you’re chuckling, too, I must tell you, humor—like God—works in a miraculous way!

©Writing With an Accent. All Rights Reserved

A Beacon of Knowledge

A Beacon of Knowledge